Written By Nik Koulogeorge

Written By

Published

Jan. 20, 2020

Updated

Nov. 21, 2021

Nothing is as simple as good and evil. We can acknowledge that the desegregation and erosion of religious affiliation of fraternities are a net-positive. At the same time, we can openly consider that the rapidity of those changes (~10 years) resulted in some unintended consequences. The purpose of this article is not to place blame, but to explain why fraternities still suffer from racial issues and segregation long after they were desegregated on paper. Most fraternity histories only highlight the fact that segregation was overcome. Few explain the debate around desegregation or the actions of those who wished to maintain segregation after desegregation was achieved.

I wrote on this site that fraternity/sorority umbrella associations and professionals maintain racial and gender segregation of our organizations in the modern world. I also explained that many of the policies, programs, and expectations we put into place to combat discrimination make our organizations less accessible or interesting for a variety of college students. This article offers some historical context. It is not complete.

Some studies suggest that there are benefits to homogeneity in a group or society. That is not to say anything of the cost of homogeneity, just that there are observed or perceived benefits. Homogeneous societies are still held on a pedestal (See: Sweden, Iceland & Japan)

Most fraternities and sororities were founded at homogeneous colleges. So, for example, it would be unusual for students at an all-Christian, all-white, all-female school to start a sorority open to black men. As fraternities grew, inter/national organizations were established to maintain common standards of membership. When my fraternity (Delta Sigma Phi) was Christian, white, and male, for example, chapter officers would send a picture of each potential member, a letter of recommendation, and a short biography to the fraternity's national secretary or a national volunteer. The secretary/volunteer would make sure that each man met the basic expectations of membership, and then give the chapter the "OK" to initiate them.

Alumni volunteers visited chapters in their district or region to ensure that the members lived up to the standards and were good representations of the Fraternity. This is an essential element of our segregated, more homogeneous pasts: fraternity leaders and alumni could assume that the social expectations of the fraternity would be reinforced by a member's family, school, weekly services, etc. Every element of their life reinforced the membership standards of the fraternity. That meant that the social expectations of a fraternity member were no different than that of other members of the same ethnicity, religion, and gender. The fraternity was a social outlet and another support system to reinforce those societal expectations.

In this way, the expectations of fraternities could be simple. For example, my chapter at Stetson University used to put on a play once or twice a year, host literary meetings/social functions, and would throw a banquet at the end of the year (which was a formal dance and recognition ceremony). Those programming requirements - if they were even required - pale in comparison to the number of expectations placed upon fraternity chapters today.

Many state and local governments tried to limit the spread of college fraternities. So, chapters increasingly turned to their inter/national leaders to protect their organizations. This culminated in the creation of fraternity umbrella associations. The National Panhellenic Conference (est. 1902 - NPC - white women), North-American Interfraternity Conference (est. 1909 - NIC - white men), and National Pan-Hellenic Council (est. 1930 - NPHC - black men and women) were established with such intents. They rooted their responsibility to protect their respective member organizations' standards in free speech and free association.

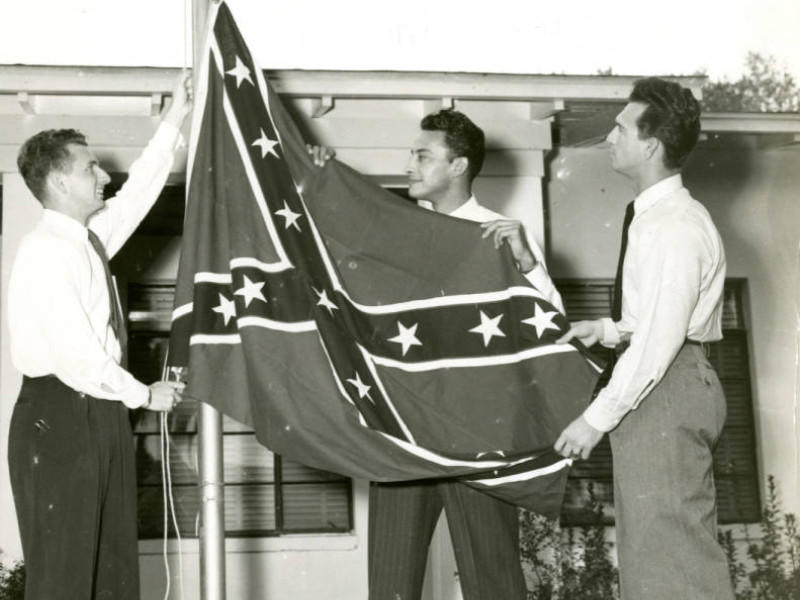

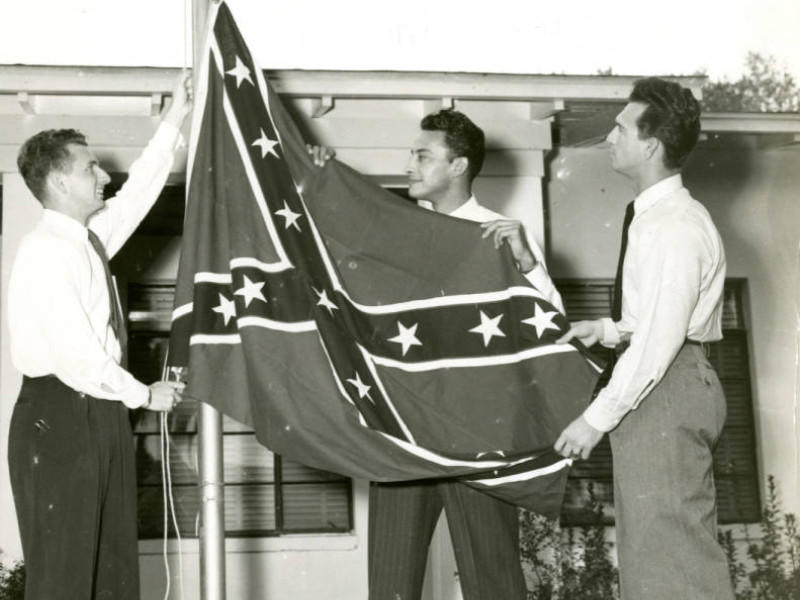

Those inter/national organizations succeeded in protecting their organizations for many decades. But times were changing, and there was a national movement to desegregate colleges and the fraternities which sprung from them. This marked what is probably the first true, interfraternal battle to preserve identity rights (which happened to be segregationist).

Although much of the story of fraternity desegregation took place in courtrooms and legislative chambers, we should not overlook the heroes of this movement: student chapters and voting delegates. Faced with "zero-tolerance" policies from their inter/national organizations, many chapters openly challenged their respective fraternity's membership standards. Chapters would initiate - or try to initiate - men of other religions or ethnicities. Additionally, campaigns at fraternity conventions to desegregate our organizations were led primarily by student members. In many cases, these votes took place well before courts took action. (That is not to say that students were unified in their opposition to desegregation, only that they were essential in passing reforms through fraternity democratic organizational processes.)

In this way, inter/national fraternity leaders failed in their role to protect the simple, objective, but segregationist membership standards of their organizations. Worse than that - for them - was the fact that much of the damage was done from within. Members organized to flex their legislative muscle, working with external actors like schools and governments to make their voices heard. Many of us have experienced the horrifying feeling of losing control. It can happen when a car spins in circles on the ice, when one receives a grim diagnosis, or with the loss of a loved one. In such cases, we can easily "overcorrect." We wildly spin the steering wheel in the opposite direction or turn to substances to heal our emotional pain.

Fraternity leaders failed in their mission to protect segregationist standards and lost their organizational identities. It is not hard to believe that those who wished to maintain segregation fought to do so - to protect their organizations - at all costs. We know this is true because many fraternities simply moved their segregationist membership criteria from their public governing documents to their rituals. These were eventually brought up in court, and those fraternities were forced to change their ritual documents. Are we to believe that the segregationists stopped at that point? How else could they maintain a sense of homogeneity without drawing attention to their efforts?

The erosion of religious affiliation was a slower, but concurrent process. It can be attributed to similar social factors as racial/ethnic desegregation. As schools opened their doors to students from a greater variety of backgrounds, fraternity men started to make friends with people who weren't allowed in their organization. So fraternities lost religious homogeneity along with ethnic homogeneity. We must treat these two equally when we discuss the "desegregation" of fraternities, because religious affiliation was as much a part of our former identities as ethnic homogeneity.

Let's dive further into what inter/national fraternity leaders may have lost in the battle over desegregation and what fraternity leaders may have done to correct what was lost. (I am using those words - "correct" and "lost" - loosely.)

They lost simple, objective standards of membership - standards that were reinforced by a members' parents, school, and place of worship.

Desegregation invalidated the existence of inter/national fraternities and their umbrella associations - so these organizations lost their purpose.

To remedy these losses and protect inter/national fraternities, [mostly the white] fraternity leaders had to exert some control. How could they do that?

Establish legally sound (read: complex) standards which would replicate simple, segregationist standards.

Replace the role of a community (parents, school, church) to reinforce those standards in each members' day-to-day life. This would serve to protect inter/national organizations and umbrella associations as they were now the covert maintainers and educators of these new standards.

"The power to protect implied the power to control. And the power to control included the power to destroy" - Robert Meacham in American Lion

Inter/national fraternities still serve to protect their chapters, but the relationship is coercive, even if fraternity/sorority leaders don't admit it. Every new policy or addition to a chapter's checklist of expectations is accompanied by a threat. A chapter that fails to complete the checklist might lose recognition from the fraternity or school. Violate any of the risk policies and your chapter loses its insurance coverage (and probably its charter).

We can most clearly see this authoritarian complex in our current fight against hazing. Our efforts to control students fail because they are impractical, particularly when one considers the federal structure of a fraternity. It is unrealistic to expect that a college fraternity could replace the communities which naturally reinforced the old standards of membership. Our standards are too esoteric, too abstract, and too sloppily translated into "public values" to make sense to the outside world. Inter/national fraternities and fraternal umbrella associations still exist to protect fraternity organizations. But that role has been warped and manipulated to control undergraduate students and to protect inter/national and interfraternal organizations at the expense of the students.

I do not believe that modern fraternity leaders are in favor of racial segregation. We commonly believe that it is important to have spaces for women, Black Americans, and other minority groups. But we cannot and should not continue to blame fraternity students - specifically those affiliated with historically white organizations - for the continued formal segregation of our organizations by umbrella associations and councils.

Furthermore, we cannot look past the fact that the expectations we set are designed to turn students away from the fraternity experience. Our standards make it difficult or impossible for low-income students, students with families, and students with jobs to find a home in our organizations. If we wish to see greater diversity in the world of fraternities, we should look at the rules, programs, and policies put in place after desegregation and take note of which may lead to continued segregation. We should consider that our heavy-handed control over what qualifies as a fraternity organization, who can start a fraternity organization, and how they are allowed to start it, do more to keep the fraternity experience homogenized than a single group of elitist students at any one school.

Help keep it going and growing by contributing as little as $2. (Links below will take you to a secure payment portal via Stripe)

A free way to support: Subscribe to the Fraternity Man newsletter for [very occasional] updates and giveaways.